A mechanism where players must use resources from a shared pool although playing a competitive game.

Many games have resources, and many of those games have resources that, once collected or obtained, remain the property of a single player. There may be ways of stealing, forcing discards, or other ways of interacting with another player’s resource stash, but the resources (sheep, energy, coins, brains, etc) are generally only to be used by the owning player. Something a little less common, however, is restricting players to use resources from a common pool.

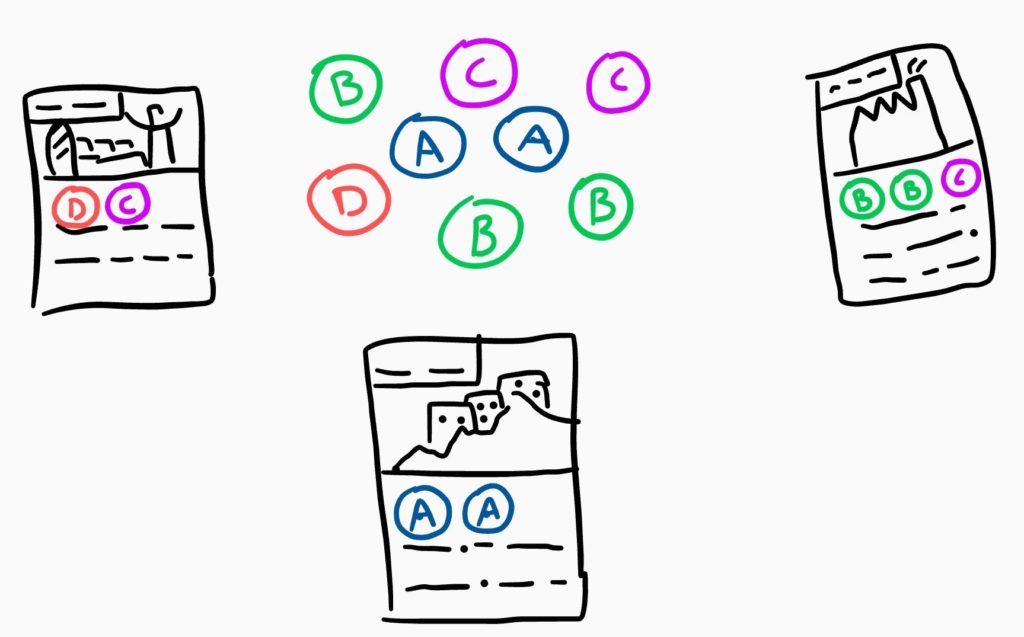

A common resource pool increases the amount of indirect action between player, and can help add interest to decision making (“Do I draw a resource to help me, or do I draw in a way to block my opponent?”). By “common resource pool”, I mean that any resource in the pool is able to be taken by any player on his or her turn. Thematically, this resource mechanism might be found in a fledgling lunar colony, or some other kind of growing entity where competing factions nominally have to work together. Looking back to the example image above, the left player has a card that requires a “D” resource – if the bottom player knowns this, he can draw the only “D” and block the left player from playing his card.

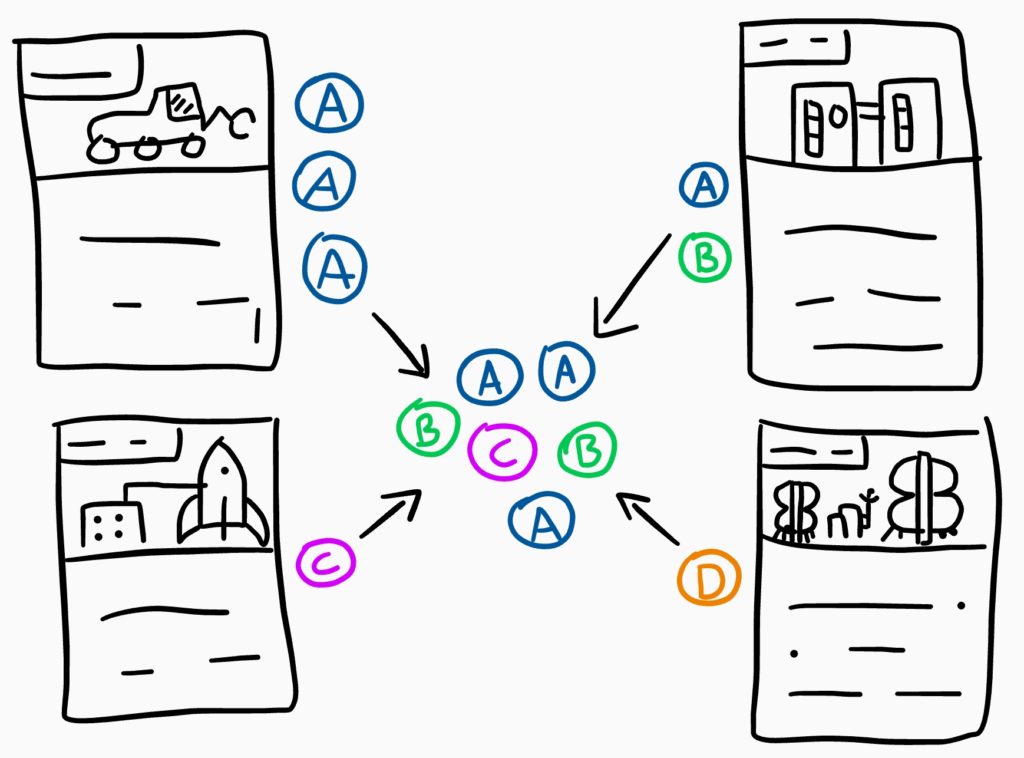

To increase a player’s decision space, the type and amount of resources allowed to be drawn on a given player’s turn can be governed by what abilities or structures that player has in play. For example, increasing one’s economy or manufacturing prowess could grant extra resources to be drawn. Perhaps scientific advances allow access to rarer resources that are only used to purchase exotic or high-end abilities or structures – see examples below:

This common pool could be replenished in a variety of ways:

1. On a preset schedule. This could be fixed for the entire game, or perhaps as turns go by, certain resources become more plentiful while others dwindle. For replayability, the schedule could vary each game. For example, if the game focused on colonizing the moons of Jupiter, maybe each moon has a different resource schedule, thereby changing the strategy from game to game. Knowing this schedule increases a player’s certainty of what resources might be available to draw on his or her turn.

2. Based on players’ cards or structures. Going back to the example theme of competing factions in a fledging lunar colony, these structures could include solar power plants producing energy resources, algae farms producing food, or oxygen plants making air. To make things even more interesting, some resources could be produced more readily (greater amounts produced per structure or just more structures that make this resource). Deliberately planned scarcity can make for different winning strategies, which increase deployability and deepens the player’s decision space.

3. Based on what player’s turn back in after spending. As players draw resources and then spend them, the resources simply go back into the common pool. This creates a bit of a tailwind for players that are “downstream” of the active player because their resource pool will substantially larger – potentially a good balancing effect. This replenishment variant can make the game feel less thematic – why am I able to collect the energy or food or steel that the player before me just spent?

Some things to think about with a turn-based common resource pool mechanism:

- Once the player count increases from 2, the players no longer have a good idea of what resources will be left when it is there turn to play. Depending on how your game should feel regarding strategy (long-view decisions) versus (short-view decision), this uncertainty may not be desirable.

- Hoarding resources may become a dominant strategy. An easy way to dissuade players from doing this is to charge some cost for storing resources. Perhaps resources must be stored in an expensive warehouse, or there is some kind of victory point cost for resources that are drawn from the pool but not immediately used.