A game mechanic in which players must choose actions that may benefit their opponent.

Many games have direct interaction between players as a result of deliberate “take that” actions, such as “lose 2 random cards from your hand”. Other games have indirect interaction caused by one person taking the resources needed by another player, or choosing an important action, thereby blocking others from also choosing it.

Player interaction is almost always a good thing, but it usually boils down into one of the two categories above. One way to introduce a different twist to player interaction is to have players interact with each other positively, despite playing a pure competitive game. The way to do this? Simply require players to select an action for their opponent instead of themselves, especially if the actions available are usually positive.

For example, imagine a game where players are randomly dealt cards, each of which depicts a certain action. Let’s say that each round, a player is given three cards to make a decision about. One card must be played facedown, indicating it is intended to benefit the owner. A second card is discarded to a central pile, yielding no effect. The third card, however, is given facedown to the opponent. Once both players have assigned their cards, the facedown cards are flipped and resolved.

The key tension to a mechanic like this is that a player is frequently forced to play cards that are helpful to his opponent. Deciding between a good choice and a mediocre choice for one person is a trivial decision, and one that likely won’t interest a player for long. By linking two people into one decision, however, the game now puts both players on the horns of a very interesting dilemma.

“Do I play a good move for myself and risk giving my opponent a great move, or do I settle for a mediocre play for myself and give my opponent a card that is simply neutral or negligibly positive?”

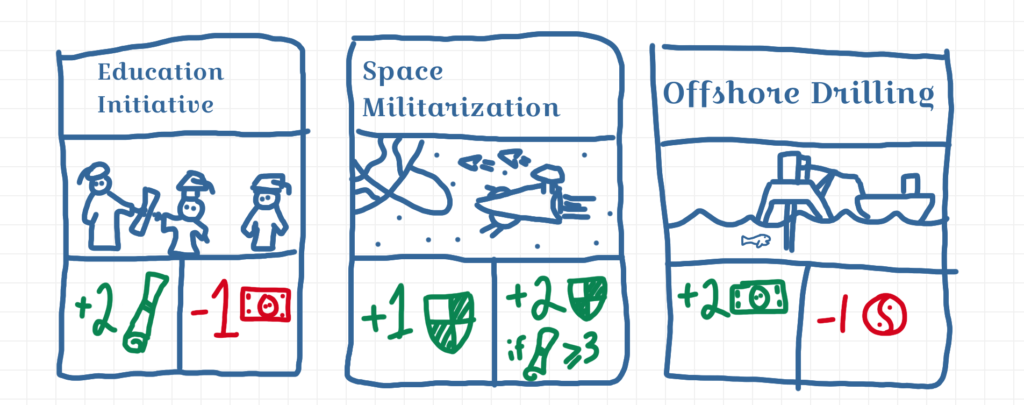

Let’s put the idea in a game: In a nation-building game, perhaps these cards have a range of effects on the nation’s overall character. Maybe the Education Initiative card provides +2 Education but also -1 Economy. A Space Militarization card normally provides +1 Military, but could grant +2 Military if the Education level is 3 or higher. The Debt Forgiveness card gives +1 Diplomacy but costs -1 Economy. An Offshore Drilling effort may results in -1 Diplomacy, but +2 Economy.

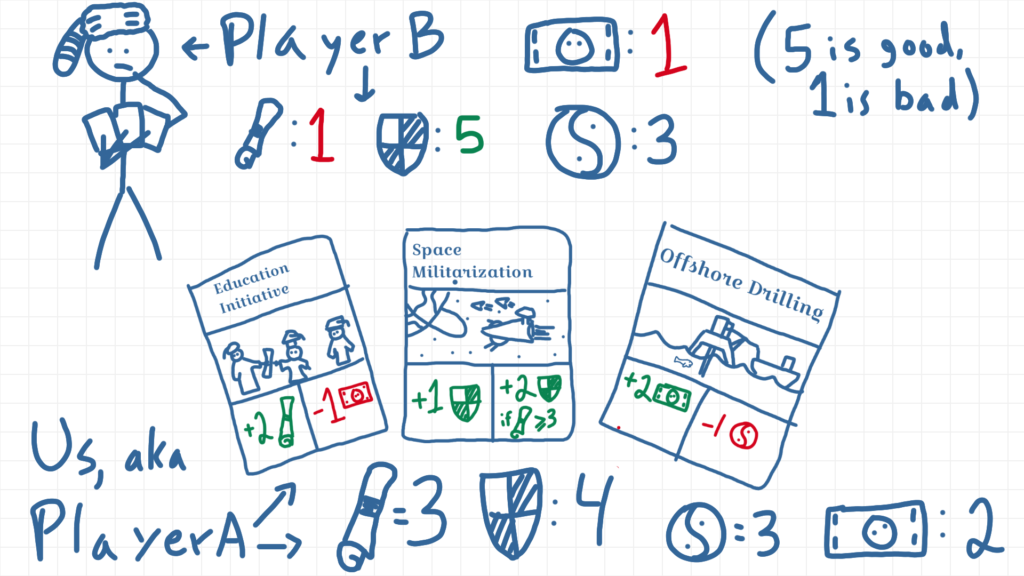

Look below: if Player A is looking at a hand of three cards, Education Initiative, Space Militarization, and Offshore Drilling, he must take a close look at both his own nation’s status, but also his opponent’s. If Player A’s Education is slightly ahead of Player B’s, it might be a losing move to give Player B the Education Initiative since it would jeopardize A’s advantage in Education. Similarly, Offshore Drilling might be bad because it will enhance B’s Economy (which is weak) significantly more than it will hurt his mid-rate Diplomacy (or whatever my yin-yang icon represents). That leaves Space Militarization; although it is a card with no costs, it also gives the least benefit to B, assuming that there is no special advantage to having 6 Military or an certain amount greater than the opponent.

It might help to have special benefits or penalties that occur when a player reaches a particular high or low in a certain currency. In this example, you immediately lose if you even reach 0 Military, but there are no strong reasons to maintain a large Military. If our Player B ever found himself with just 1 Military, it makes Player A’s likely to give B a card that incurs a -1 Military cost. Similarly, if having an Education level 3 or more above your opponent lets you play a second card for yourself each turn, that gives both players an area to focus on when that situation is on the verge of occurring.

If the players in this game are choosing and then revealing actions simultaneously, you also get to introduce a bit of “I know that he knows that I know…” mental churn. It is usually great fun when you successfully get inside your opponent’s head, but both players will need to know what cards the other player is looking at. Requiring an open hand might not fit for your game, and if that is the case, you still get a benefit from simultaneously revealing chosen cards because the net change of any particular round is the combination of both the card you picked for yourself, and the card your opponent picked.

The trick to making a mechanic like this appealing is to give players two or more simple yet agonizing decisions to choose between. Complexity reduces the obviousness of struggling through a dilemma, so strive for clear, perhaps even binary (or trinary in this example), decisions. Like any game, this one will need a fair amount of balancing to make sure that there aren’t dominant strategies (for example, “always give the opponent cards that decrease his Economy”). Using spreadsheets to mathematically balance a distribution of cards is a solid way to ensure that there aren’t any numerically likely avenues to success.